The Jackie Clarke Collection | Opening hours: Tuesday to Saturday 10am - 5pm | Free Admission

Our Blog

News and items of interest from the Clarke Collection

Popular Tags

Ida O’Hora -McGrath; Ballina’s Soldier of Cumann na mBan

In early January 1945, Pheilim Calleary, future TD for North Mayo, penned a handwritten letter of support to the Military Service Pensions Board on a behalf of a Ballina woman, well known to him from his days of active service with the North Mayo Brigade of the Old IRA.

In his letter he stated “…this lady was the best in the…Brigade Area and the most active of Cumann na mBan in this district”

The lady in question was Mrs. Ida McGrath (neé O’Hora) of Garden Street and later Pearse Street Ballina, and wife of Martin J. McGrath. Calleary was in no way overstating the case of this formidable woman, whose lengthy pension application has recently been made available by Bureau of Military History. These remarkable files reveal the fascinating tale of a daughter of Ballina who made a strike for Ireland’s freedom, one hundred years ago.

Ida was born to Michael and Kate O’ Hora in 1899, the second eldest of four children. She attended school at Ballina’s Covent of Mercy. The 1911 Census shows Ida’s widowed mother Kate as the head of household and proprietress of a small grocery shop in no. 3 Garden Street. Ida was just 12 years old and could not have foreseen that in the decade which followed, she would be at the centre of an unprecedented period in Irish history, which played out in a most dramatic fashion on the streets of Ballina.

In 1918, at just nineteen years old, Ida set up the Ballina branch of Cumann na mBan- the women’s organ of the Irish Volunteers which pledged to support, fund and ultimately fight for Irish freedom. She was President of the Ballina branch, which had a membership of between seventy and 100 at any given time. She set about recruiting and organising, ensuring that branches soon sprung up in areas such as Rehins, Cloghans and Bonnicnonlon.

Ida rose to the position of O/C of the District Council. Those early days were dedicated to drilling, parading and learning essential First Aid skills. Dances and concerts were put on, an effective means of raising funds to arm the Irish Volunteers and support the campaign of the Sinn Féin Party in the historic General Election of 1918.

With the outbreak of the ‘Tan War’ in 1919, the nature of Ida’s activities and responsibilities greatly intensified. By this time, she had taken up employment in Walsh’s Stationery and Tobacconist store on Knox Street. She lived nearby on the same street. Walsh’s shop was to become more than just a place of work for Ida. As time went on, the premises fronted as a pick-up and drop-off point for dispatches, intelligence reports and weapons for various members the North Mayo Brigade. Dr. John Crowley of Ballycastle was a regular visitor. There was considerable risk involved, given the proximity of the RIC Barracks on Charles Street and later the billeting of the notorious ‘Black and Tans’ at the Moy Hotel, on the very same street. Ida regularly stored caches of revolvers and ammunition under some loose floorboards on the stairs of the shop- “I had a little place”, she wryly told the pension board interviewer.

With the help of local Brigade member named Waters, she even managed to secure a revolver and three bandoliers of ammunition from a member of the Auxiliary RIC named Nangle, stationed in the Ballina Barracks. Her own home-which doubled as a ‘safe-house’ was raided on several occasions, but as nothing was ever found, Ida continued in her work, undeterred. Half-days, evenings, weekends and every spare moment was spent carrying dispatches and weapons all over North Mayo, often accompanied by her younger sister Florrie, who tragically died in 1926 as a result of TB. A third sister, Bertha, was also an active member of the Ballina branch of Cumann na mBan. Bertha married prominent local Brigade member Willie Lydon in December 1923.

Parcels of clothing, food and cigarettes were made up and brought to men ‘on the run’ and members of the local ‘Flying Columns’. Raising much needed funds for the Prisoners Dependant Funds was a constant concern, and much of the necessary funds and provisions were supplied at Ida’s personal expense.

She was regularly dispatched to Dublin, entrusted with confidential communique between local Brigade officers and IRA Headquarters. Michael Collins was personally known to her. She was a trusted intelligence gatherer and surveyed the movements of the local Crown Forces from her vantage point in the town’s main thoroughfare. Her reports were regularly put to good use, most notably on the night of 21st July 1920, when a local column carried out a daring ambush of the RIC/Auxilary nightly patrol at Moy Lane. The engagement resulted in the fatal shooting of RIC Sergeant Robert Armstrong. Ida was in position as a scout near the Barracks on Charles Street on that fateful night.

In April 1921, Ida found herself at the centre of one the most shocking events in Ballina’s War of Independence story- the case of Michel Tolan. A 26-year-old tailor and Intelligence Officer, he was born with deformed feet. He was captured by Crown Forces on 4th April 1921 and held prisoner at the RIC Barracks in Ballina until 7th May 1921. Tolan disappeared and there was no trace of him until the body of a man bearing gunshot and bayonet wounds was discovered at Shraheen Bog, near Foxford, in June of that year. The victims’ feet had been savagely hacked off. Ida, accompanied by her good friend and comrade Margaret Sweeney, had visited Tolan on several occasions following his initial arrest and supplied him with clothing, cigarettes and meals for the three weeks of his incarceration.

Tolan had suffered a terrible beating at the hands of the Tans. To ease his suffering in that cold prison cell, Ida brought him warm clothes, woollen socks and a dark green overcoat. This last item of clothing was to become a key piece of evidence in the inquest into Tolan’s murder in November 1921-the description of the coat worn by the victim found at Shraheen matched that of the one supplied by Ida. As one of the last persons to see him alive, her evidence at the inquest- which returned a verdict of ‘Wilful Murder at the Hands of Crown Forces’- was pivotal.

In July 1921 Ida was sent to Castlebar by train to fetch Dr. McBride, who was needed to perform surgery on Volunteer Jim Devaney. Devaney was badly injured in the ambush of an RIC patrol at Culleens, Co. Sligo on 1st July 1921 and taken to the home of Mary Ann Morrison at Ballyherane, Rehins. Mary Ann was Captain of the Rehins Branch of Cumann na mBan. Ida continued to visit the home of Mary Ann and assist in the care of the wounded man for a full month. The Morrison home was a reliable ‘safe-house’ and sheltered a constant steam of IRA men evading capture throughout those turbulent years. It was one of countless such tasks undertaken by the women of Cumann an mBan across the land, whose crucial role in the Revolutionary period is beyond measure.

The calling of a Truce between Great Britain and Ireland on 11th July 1921 did not signal a return to quiet civilian life for Ida. She continued organising and recruiting for the Cumann na mBan branches under her remit in the district. She was visited by Miss Plunkett, a high- ranking organiser from Dublin, and three new branches, in Moygownagh, Crossmolina and Lahardane were set up.

Ida opposed the Anglo-Irish Treaty negotiated in London in December 1921 and thus took the Republican side in the bitter ‘parting of the ways’ which followed. She was appointed a Special Intelligence Officer in the IRA- a testament to the high esteem in which she was held by her fellow male comrades-in-arms. During that tumultuous Civil War period, she carried dispatches for the Republican IRA “every other day”. She set about procuring weapons and ammunition from a most unlikely source- a Free State Officer stationed in the town. With the help of her brother-in-law Willie Lydon, a revolver, a Lee Enfield rifle and ammunition were purchased with Ida’s own monies in support of the Republican cause. Ida’s dangerous espionage work continued as before. The nature of the enemy may have changed, but the risk was as great as ever. Her intelligence reports were vital to the success of the Republican Capture of Ballina in September 1922.

On the morning of 1st March 1923, local Brigade Quarter-Master Denis Sheerin was captured by Free State soldiers. A search of his pockets revealed a dispatch addressed to Ida O’ Hora. At 11am, her home was raided, and Ida was arrested. She was transported to Kilmainham Gaol, where she began an arduous 21-month sentence. The’ Cumann na nBan corridor’ was located on the top floor of the extension added to accommodate female prisoners in the 1840’s. Conditions in the Victorian prison were notoriously abysmal. Inmates were forced to share cold, dimly lit cramped 28- square- metre cells with several others. The harsh treatment of the female Republican prisoners during the Civil War is well documented. Insufficient food rations, frequent searchers in the middle of the night and other tactics of intimidation, designed to break the morale of the prisoners, were the order of the day.

In May 1923, Ida was among a group on prisoners transferred to North Dublin Union-a derelict former workhouse used to house prisoners during the Civil War - where she served out the remainder of her sentence. Those dark days of imprisonment in Dublin brought her into contact with women of national prominence such as Nora Conolly, Grace Giffford-Plunkett and Mary Mac Swiney, to name but a few.

In her interview to the Pension Boards, Ida does not give any details of her time as Republican internee other than to clarify the dates of her incarceration. Indeed, the interviewer added a note alluding to Ida’s modesty, remarking ‘Applicant does not overstate her case, which appears to be a very good one.” Perhaps there was more to be gleaned from what Ida left unsaid.

The archives of Kilmainham Gaol are home to a number of Prisoner Autograph books, which have survived form the period. These little booklets contain names, drawings, verses and slogans carefully added by inmates. They were a way of passing the time, recording their experience and expressing political ideologies. Among these faded pages of history, Ida O’Hora’s neat handwriting can be found.

In May 1923, from Cell 28, A-Wing Kilmainham Gaol, Miss Ida O’Hora, Prisoner 142, inscribed her name and Pearse Street Ballina address in the autograph book of fellow inmate and Tralee native, Hannah O’Connor. Ida added lines quoting PH Pearse: “Ireland unfree shall never be at peace”. In June 1923, from her cell in North Dublin Union (NDU), she evoked the words of Terrance Mac Sweeney, the Lord Mayor of Cork who had died following a 74-day hunger strike in Brixton Prison in October 1920; “Not those who inflict most but those who can endure most will prevail (sic.)”.

Following her release, she returned to her hometown, beginning her new life as a civilian in the new Free State.

In Spring 1938, Ida married fellow Ballina native and former prominent member of the North Brigade, Martin J. Mc Grath. Martin was well known and respected in the town. He served successive terms as Chairman of Mayo Council, Irish Tourist Board representative and was part the Ballina Stepehenites Park Fundraising Delegation which travelled to America in the mid 1960’s.

Ida and Martin operated a newsagent’s shop on upper Pearse Street, in premises that was later McGonigles chemist, noted as one of the narrowest shops in the town. Martin entered the auctioneering business in 1951 and Ida held the position of Old Age Pensions Clerk for the county for many consecutive years.

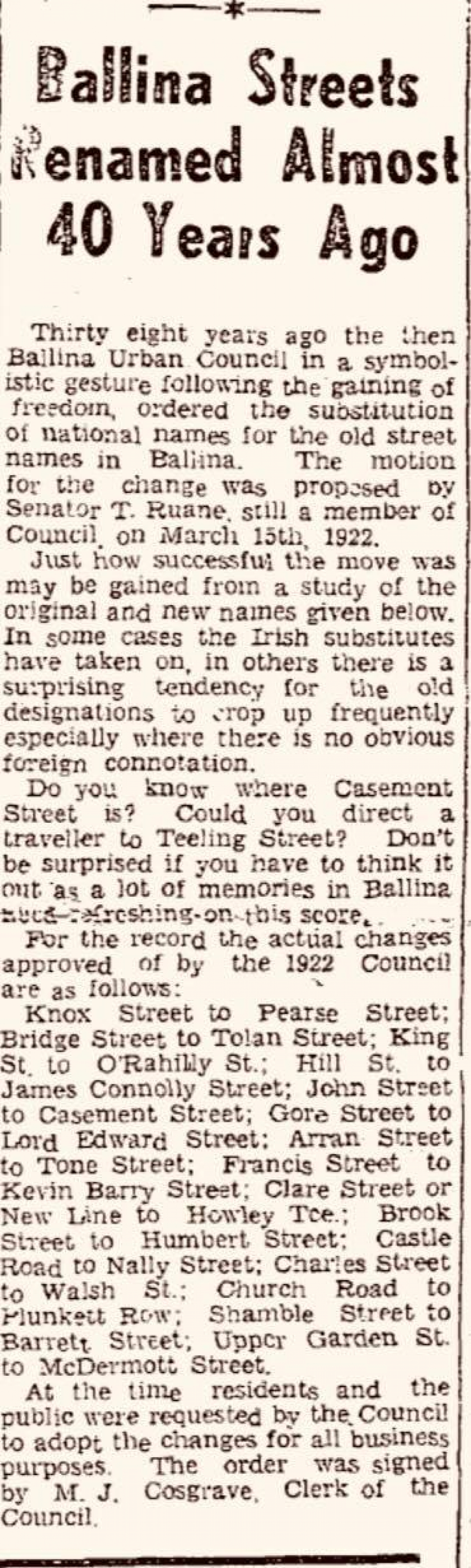

In her later years, she was a familiar sight to passer-by’s going about their business in Pearse Street, formerly Knox Street- a street which was the constant backdrop for so much of Ida’s fascinating life. Local Ballina men Tom Mitchell and Paddy Gorman recall their memories of Ida in her twilight years, in her home on the lower end of the street, near the site of Ballina’s Tourist Office. Tom was employed as a messenger boy for Lowry’s Grocery Store in the early 1960’s. Paddy also did a stint as a busy messenger boy and worked for Gavin’s in the mid-1960’s.

Both remember Ida sitting on a chair inside the window, the bottom half of which was always lifted up. ‘She would nab you to do a few little messages up the town’, Paddy remembers. Tom adds, ‘She would have a little chat and always give a good tip’. Both men call to mind a small, kindly woman who seemed older in years than she really was- perhaps the hardships endured in previous decades had taken their toll.

Ida O’Hora McGrath died in St. Joseph’s Hospital Ballina on the 11thAugust 1966, the year which marked the fiftieth anniversary of the 1916 Rising. Ballina commemorated the occasion with a large procession and the unveiling of a new memorial at the Republican Plot in Liegue Cemetery, not far from where Ida and Martin (d.1974) are laid to rest.

I wonder, what did Ida make of it all? Had the new Ireland she risked her life for been achieved, and what would she say of Ireland in 2021?

Her funeral at St. Muredach’s Cathedral drew large crowds. Full military honours were given. The tricolour which draped the coffin was that which had been used at the funeral of Maud Gonne, thirteen years previously. The graveside oration was given by Phelim Calleary (by now a TD for Mayo North). “Never will there be”, he remarked, “another fighting lady in the War of Independence like dear old Ida”.

Fifty-five years have now passed since Ida O’Hora- McGrath went to her eternal rest. Her name and heroism have been somewhat overlooked in recent times.

This evening, when I leave the Jackie Clarke Collection and pull closed the heavy front door of the former Provincial Bank, I will be just stone’s throw across the road from the site of Ida’s last home on our town’s main street, where she sat with the window half open and often beckoned my father on his messenger-boys’ bike to ‘do a little message for me…” all those years ago.

There is no plaque for Ida in Ballina; no street will bear her name.

Perhaps the words of the Brian O’Higgins song ‘The Soldiers of Cumann na nBan’-one of only a handful of verses written for the women of that brave generation- will spring to mind as I lock the gate and make my way down Pearse Street:

“But do not forget in your praising,

Of them and the deeds they have done,

Their loyal and true-hearted comrades,

The soldiers of Cumann na mBan…”

Do not forget Ida…

Ballina’s brave soldier of Cumann na mBan.

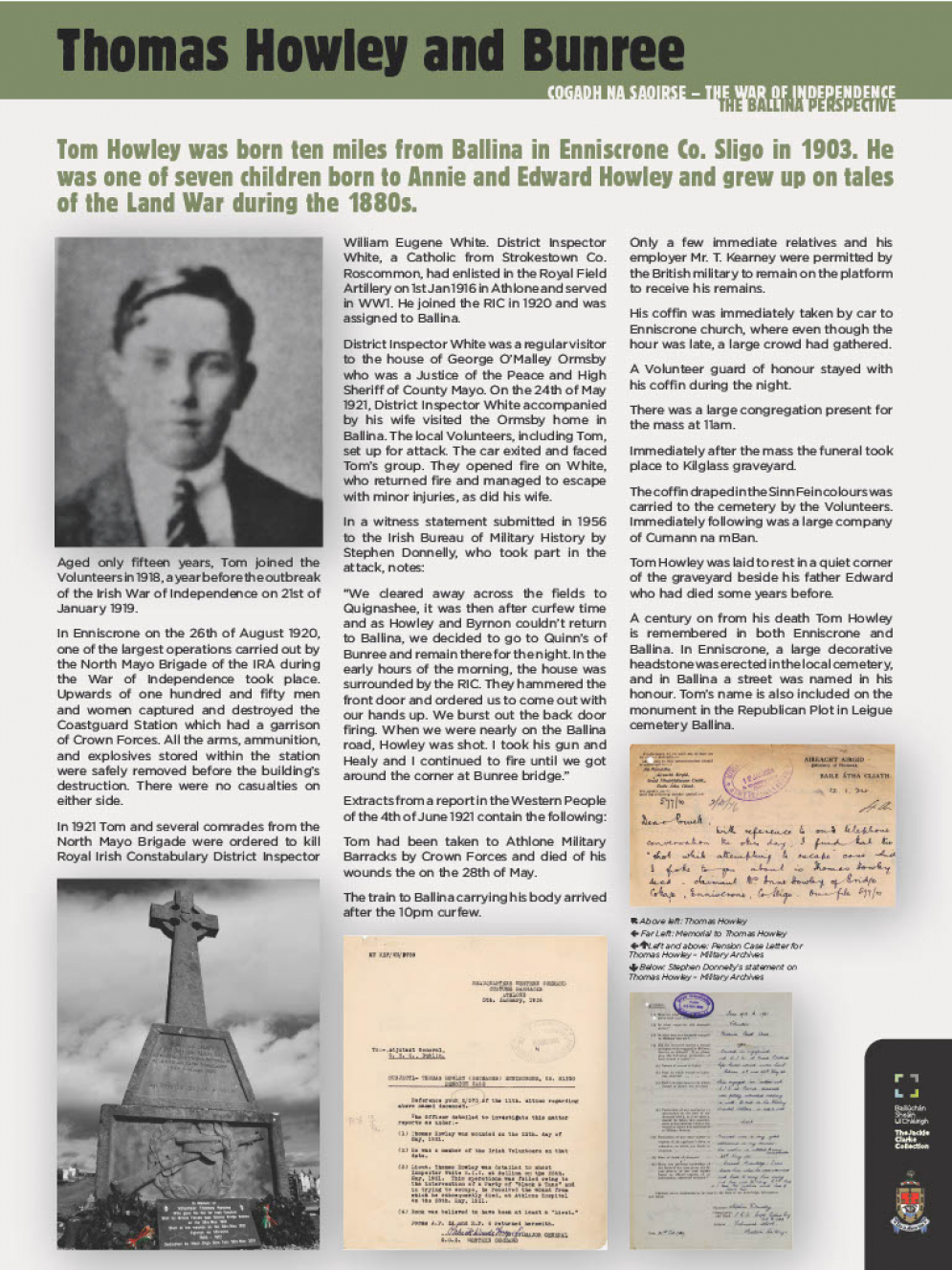

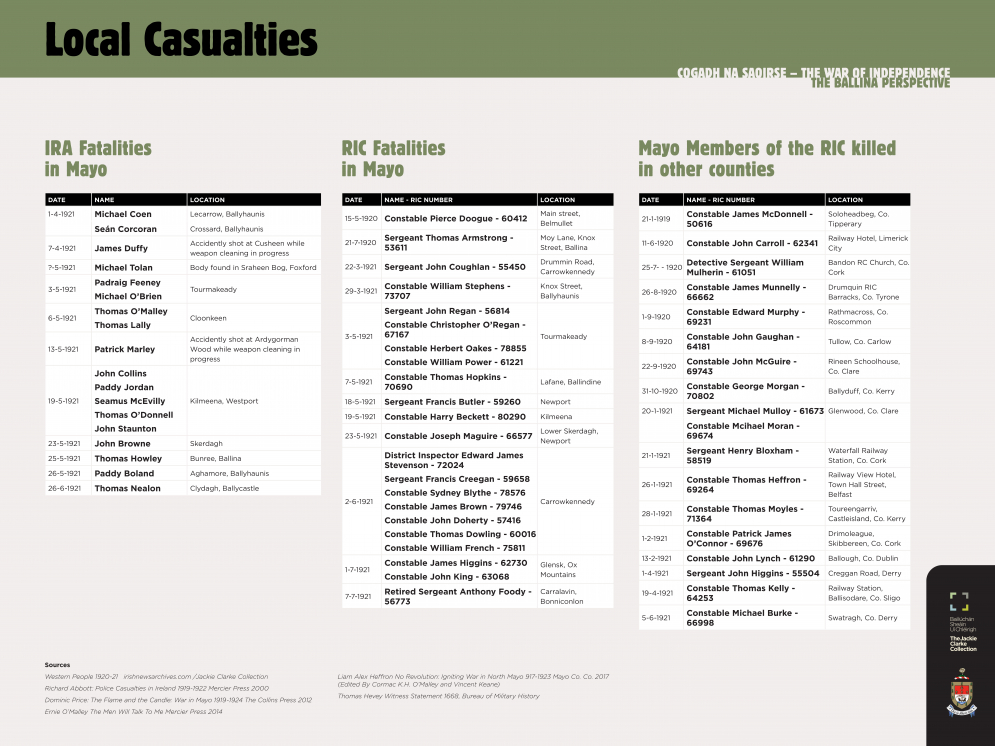

National Heritage Week, running from August 14th to 22nd, an initiative by the Heritage Council, celebrates all things heritage! In conjunction with this important week on the heritage calendar, the Jackie Clarke Collection is proud to present an exhibition on the Irish War of Independence; Cogadh na Saoirse - The War of Independence - The Ballina Perspective. The panel exhibition will be on display in the Jackie Clarke Collection from next week but for those unable to visit the Collection at this time we will be releasing content from the exhibition all this week online to celebrate National Heritage Week. The exhibition focuses on a selection of some of the local people and incidents that occurred in Ballina and its environs from 1919 to 1921. The project, including extensive research and content writing, was a collaboration between the Jackie Clarke Collection and its Volunteer and Education programmes. We begin the online release of the exhibition with the list of local casualties.

Frank Fagan © MA Local History UCC 2021

In Memory of an Ambush

Above: Photograph (courtesy Tuffy Family) of the original Tuffy's shop in Culleens, the scene of the dramatic ambush on 1st July 1921.

Introduction

“You must understand, I have no memory of these events, I only know what I have been told about them.”[1]

I am sitting in the kitchen of a house in an estate in Castlebar in March 2018, across the table from me sits Pat Ruane. I had contacted his wife a week before to see if he would be willing to speak to me about a shooting incident which took place on the 29th of June 1922 in Kiltimagh, Co. Mayo. Pats wife Mary called me back and said that he would be happy for me to visit, accompanying me was my colleague Sinead from the Jackie Clarke Collection in Ballina.[2] I have learnt in such circumstances, that time is of the essence and was eager to meet with him and hear what he had to say. As we drove to Castlebar, we discussed how to approach the interview. I was insistent that our focus would be the events of 29th of June 1922, but I knew that there was another incident that might surface.

I had discovered Pat Ruane’s family background and connection to the Civil War shortly before our meeting, while researching a presentation I would give to local people who were interested in using the Military Archives Website. During the course of my research I found a pension application for Willie Moran from Bohola who had been shot dead in Kiltimagh on the 29th of June 1922, I could see from the application that there were two other files linked to this incident. One was for Tom Ruane (Pat’s uncle) who was mortally wounded on the day and died five days later and the other was for James Ruane (Pat’s father) who was shot and badly wounded but survived. The Ruane brothers had joined the Free State army and had been recruiting local men when a number of armed Republicans including Willie Moran had entered the crowded pub and shop owned by the Ruane family to arrest the brothers, within minutes the incident had escalated and resulted in the deaths of two men.

Over the course of the couple of hours that we spent with Pat, he discussed in detail all that he knew about this incident, including the fact that his father had followed the man who killed his uncle to Alaska but lost his trail there. I was fascinated by the fact that Pat knew so much, but as he reminded me, he only knew what others had told him.

As we came near to the end of our meeting with Pat, and as I had expected, he began to speak about another incident which took place in the same premises in Kiltimagh twenty two years later, on the night of 18th of May 1944. In the early hours of the morning, a mysterious fire[3] completely destroyed the building and resulted in the deaths of eight people, including Pats mother, father, seven year old brother Thomas, six year old sister Bridget, and five year old brother James. Pat was eighteen months old at the time, he was thrown from an upstairs window and caught by a bystander and saved.

As we drove back to Ballina in silence after our meeting with Pat, we both knew that we had just witnessed something extraordinary in every sense of the word.

Pat Ruane died five weeks after our visit. The experience of meeting him in his home has been a significant influence on my research of the Revolutionary period and highlights the importance to me of capturing the oral history before it is too late. While looking at other incidents and attacks which took place during this period involves researching the pension files, the Bureau of Military History Witness Statements, the newspaper reports and the various books that have been written about the period, I feel that I too am like Pat, in that I have no memory of these events, but only know what I have been told about them. And yet, I am also aware, that unlike previous generations of historians looking at this momentous period in Irish history I have access to first hand accounts from participants who probably never imagined that details they had submitted for pension applications in the 1920s and 1930s would at some future date become available to the public. Details in some instances that were never shared, even with close family members.

With all of this in mind, my focus now turned to another incident which also resulted in the deaths of two men, and another meeting that I had been working on for a long period of time.

In October 2018 I had invited noted Sligo historian Michael Farry to address a group of local people in Culleens west Sligo on his twenty five years of research and publications covering the Revolutionary period in the county. The venue I had chosen for his presentation had been the site of an ambush in July 1921 on an RIC patrol, which resulted in the capture and killing of two members of that patrol. The owner of the venue had requested that I give a presentation on the Culleens ambush, and I was surprised to discover how little knowledge local people had of the event and yet was also aware that some within the community had family connections and stories from that day but for whatever reasons they were only ever discussed within that small group of families. I was also aware that night by the huge turnout of the interest local people of all ages were showing in the history of their locality. Thus began my interest in the Culleens ambush which took place on Friday the 1st of July 1921.

I could find very few references to the ambush in any of the history books I had read of the period, with the exception of Michael Farry’s work[4] and an interview carried out by Ernie O’Malley.[5] Richard Abbott[6] mentions the ambush, but states that the patrol was from Ballina Barracks (the opposite direction from Dromore West and fifteen miles away) the townland of Culleens was not included. Of note is an important statistic which Richard Abbott does include in his publication, in the two months prior to the Culleens ambush, one hundred RIC members had been killed, and by years end a total of two hundred and forty seven. In Jim Herlihy’s short history of the RIC[7] I could find a one line entry in the appendices for each of the Constables killed, but no mention of Culleens, along with giving their RIC numbers and date of birth they simply stated that each man was “killed near Dromore, Co. Sligo 1/7/1921.”

I felt it was important for me as someone who has only moved to the area in the past eight years, to make contact with a family member who would share the details as told by a relative who had witnessed at first hand the events of a century ago.

The civilian memory - 96 years 9 months later

Both of my Grandfathers were Volunteers during the War of Independence and Civil War, I have a particular interest in that which is held in the memory of the Revolutionary period, or more precisely that which is still difficult to explore and examine even at this remove. The opening of archives such as the Military Service Pension applications, the Bureau of Military History and the Brigade Activity Reports are an invaluable tool for any research of the period, used in conjunction with some of the files now available from the British National Archives they can give different interpretations and insights into an incident such as the ambush that took place at Culleens. But with each of the archives, one must be aware of the different forces at play and the outcome some were hoping for in submitting an account of their role in these events. The records and archives of this period cannot be consulted without also acknowledging the substantial passage of time in some cases between the event itself and the interview, as Anne Dolan states[8] while referring to a different incident which took place during the War of Independence “But while the gap between twenty-four hours and thirty-four years might say much about the slippages of memory, about the ways something needs to be remembered, or will or not be told, the point of these two versions of one killing in the Irish War of Independence comes to something more than that. In a history of killing, who do historians choose to listen to and what are some of the consequences of that choice?”

I had heard vague mentions of an ambush close to where I now live in County Sligo but did not know any details of what had happened. I began to ask local people about the incident, but nobody would speak to me about it. The more silence I experienced on the subject, the more curious I became about what had actually happened. I persisted with my interest, and I was eventually contacted by local man Martin Wilson who is from the townland of Culleens, he told me that we would need to set aside a full day, and that he would introduce me to some older people who had family connections to the events of that day on the 1st of July 1921.

The first house we visited, in a remote area off the main road, was that of Martin John Dolphin,[9] his father was eight years of age in 1921, had witnessed the events with his sister who was two years older. One has to remember that summertime in west Sligo is a time to cut and save turf (something which still continues to this day) for the long winters, turf cutting is an integral part of community life here and also an important social occasion involving entire families which has been maintained for centuries. A large number of children would have been engaged in the work that day on the bog, they would have seen at first hand the events unfolding. Another important detail to be aware of, is that the same families have cut the same section of bog for generations. Martin John was very ill when we visited him and needed assistance to gain entry to the van we were travelling in. We left his house and drove for about thirty minutes up mountain roads and eventually came to a well-worn trail on a raised bog at the foot of the Ox mountains. Our destination would be the section which the Dolphin family were working on in the summer of 1921.

As we drove along this trail with the vast bog on either side, with no field boundaries or markers, I wondered to myself (as a Dublin man) how you could find anything in this place. Martin John signalled that we needed to stop, we got out of the van and he guided us to a spot, removed some clumps of heather and revealed a small plaque which read “Pray for the souls of Thomas Higgins aged 37 years and John King aged 36 years who died here 1st of July 1921. Erected by the Higgins family.” I found it a moving experience standing on the spot, where 97 years previously two men were shot dead. I wondered what their last moments had been like. The other detail which I found incredible, was the fact that there was a six foot square of bog where the bodies had fallen that had not been cut since 1st of July 1921. This section of bog was about a metre and a half higher than the rest of the bog. I was later to find out that the day they were killed had also been a beautiful sunny day just as it was when we were there. I asked Martin John about the plaque, he told me that about fifteen years previous, he had been contacted by a local person as there was an elderly American couple inquiring in the local Post Office and shop about the ambush. He drove to where they were waiting and agreed to bring them to the site. When he stopped the car and walked them the short distance to where both men had been killed, the couple immediately fell to their knees, began to pray and cried. The couple returned to America but became aware that they were the only family members who had ever visited the site of the killings, and that there was nothing to mark the spot. They returned from America the following year, with up to twenty members of their extended family and placed the plaque on the spot where it remains today. The place where both men died is very remote and would be impossible for anyone to find without local knowledge, as the plaque is flat, it is easily concealed within the heather and barely visible until you are directly above it. This site is known to very few people, and given the sensitivities still surrounding a memorial of this nature, I have not shared the location with others. Of note too, is that the wording on the plaque is very neutral, no mention of the RIC or of the circumstances surrounding the deaths of both men. And yet, it is a powerful and poignant reminder of what happened here.

I took a number of photographs of the site, and also asked Martin John about details his father had shared with him of that day. He told me that when the British reinforcements had arrived and discovered the bodies, they fired indiscriminately at close proximity to the hundreds of civilians spread about the bog and had killed donkeys and pony’s in the process. Martin John’s father ran from the bog with his older sister and as they did, they could hear several bullets pass between them.

Having finished on the bog, we then retraced the final steps taken by RIC Constables Thomas Higgins and John King. Martin John explained that on the day, upwards of thirty five members of the North Mayo Brigade IRA had ambushed a patrol of RIC men. He explained how the ambush party had divided into two groups, he was able to show us where the groups had been positioned. One section had concealed itself on high ground beside the road which gave it a clear view of any movement for almost a mile coming from Dromore West, which was where the local RIC station was situated. He explained that in the middle of the ambush, a car had driven through on its way to Sligo and one of the RIC men managed to jump onto it and headed back to Dromore West to raise the alarm. Martin John explained that the IRA had omitted to cut the telegraph wires[10] and this was why the reinforcements arrived so quickly. He showed me a gap in the mountain which the IRA were heading to escape from the large number of Crown Forces who had descended on the bog. The local men knew every inch of this area and it was this alone which saved them.

As I listened in silence to every detail that Martin John shared with me, I felt privileged to be present in such a place, I also felt a responsibility and a need to somehow record what had happened here. I was mindful of the words I had previously read of Matt Kilcawley as he described in detail the moment that Constables King and Higgins were told that they were about to be killed.

The Republican memory - 31 years 4 months later

“We gave them a few short seconds in which to say their prayers. King pleaded hard for mercy. He made all kinds of promises, and we would have liked to let the other RIC man go free. He was younger. He pleaded hard and he cried and again pleaded with us. The others would have heard the shots.”[11]

Matt Kilcawley was from Enniscrone and a member of the North Mayo Brigade IRA he was second in command of the Active Service unit that day. Interviewed by Ernie O’Malley in November 1951, he discussed the Culleens ambush in some detail, and also reveals that the original plan had been to rob the Templeboy Post Office (in order to draw the RIC out of their barracks) which is in a different location a number of miles north of Culleens, but also much closer to the RIC barracks in Dromore West. It was Kilcawley who decided that the target of the robbery should be Tuffy’s pub and shop in Culleens. He describes in his interview how he, along with twenty five men had been camping out in the mountains and training for five weeks at this point. Under cover of darkness on the morning of 1st of July 1921 they moved in close to the ambush position and had breakfast. At 8am two of the IRA men (Jack Brennan and Thomas Loftus) entered Tuffy’s shop and carried out a robbery. The only person behind the counter at the time was the daughter of the owner. Her brother Tommy Tuffy returned to the shop at 8.45am and immediately on hearing of the robbery harnessed his horse and headed towards Dromore West to report the robbery to the RIC. The trap was now set. Once Tommy Tuffy had disappeared out of sight on the road to Dromore West, the two Volunteers who had carried out the robbery returned to the shop and handed back the money they had taken earlier, Matt Kilcawley notes that on seeing the two men return, the young lady behind the counter “went into hysterics”. The Volunteers then took over the entire property including the garden and the yard. The second group took up a position four hundred yards away on high ground which would give a clear view of the approaching RIC patrol. The Volunteers knew that the RIC would be cautious and would be riding in extended formation. The plan was that the firing would begin when the lead party of the patrol reached the shop. The Volunteers had earlier made a decision not to cut the wires as this might alert the RIC to the possibility of an ambush. The Volunteers were in their positions for a number of hours and Matt Kilcawley states that they were just about to quit when the RIC patrol were spotted in the distance. “We waited. We lay low and they came in as the Angelus rung”.[12]

As the lead group of two RIC men arrived at the shop, the ambush parties opened fire from their different vantage points. The last two of the patrol would have been almost five hundred yards from the front, they came under fire from a distance. It was at this point that the first two RIC men realised what was happening and could see that the entire building had also been taken over. They found cover near a ditch and managed to return fire before surrendering. Of the remaining members of the patrol, Matt Kilcawley states that two were badly wounded and the other two had escaped across country. As a result of the ambush the Volunteers were now in possession of an additional six rifles, two revolvers and two prisoners. Also of note in this interview were the details relating to a car driving through the ambush towards Dromore West at the height of the firing, the car was allowed to pass, but further down the road one of the RIC men who had escaped the ambush jumped on the car and had the driver take him to the RIC Barracks to raise the alarm. Just at the point where the car had driven through, from the opposite direction came Tommy Tuffy on his horse with a white handkerchief tied to the top of his whip.

At this point Matt Kilcawley describes how the ambush party needed food and drink, they took three bottles of brandy from the pub and they then set off up a boreen towards the bog which would lead them up to their base near the Ox mountains. After a short while they came under fire from a long distance away. They returned fire and immediately began to run until they reached a bog road “the bog was filled with people for the first three miles of it and they were cutting turf.”

Now heading at pace towards the gap in the mountains, the ambush party could see four lorries of Auxiliaries and RIC arrive behind them at a distance of only half a mile. Matt Kilcawley describes what happened next, he said that the men had a short council of war and decided to shoot the two RIC men. He states that the reinforcements pursuing them would have heard the fatal shots, that both men were left dying and that the last word he would hear John King say was “Enniscrone”.

The remainder of the interview covers how the ambush party managed to eventually escape from the RIC and Crown Forces who had by this time saturated the area. The difficult terrain and local knowledge had favoured the Volunteers. By nightfall the group had safely divided into two, one section would stay in a dugout in the townland of Clunshoo and the other in Ardvally.

A number of the ambush party were from Enniscrone, and in the days following the events at Culleens, fear of reprisals were very real indeed. To this end, the local Enniscrone Volunteers lay in wait each night for what they felt would be the inevitable attack on the village. The expected attack never happened and the political and military landscape of the country would change within ten days of the Culleens ambush, on the 11th of July 1921.

The Republican memory - 15 years 6 months later

Q. You were in the Culleens ambush?

A. Yes.

Q. What part did you take in that ambush?

A. I don’t know whether I should say it or not but I shot the two policemen that were in it.

Edward Gildea[13] from Enniscrone Co. Sligo appeared before the Military Service Pensions Board on the sixth of January 1937. Two years previously on the 8th of April 1935 he had completed and submitted his Military Service Pension application. Edward Gildea had served in the British Navy for 7 years before joining the North Mayo Brigade of the IRA in 1920. He provided invaluable arms training to the local Enniscrone Volunteers and was an active participant in several attacks during the summer of 1920. On the 26th of August that year he was one of over 150 Volunteers who captured and destroyed the Enniscrone Coastguard Station which had a garrison of British Military. All of the weapons and a quantity of explosives were successfully removed from the station and transported to an arms dump outside Bonniconlon. Three local men were arrested a number of days later for their part in this attack and would face a court martial in Belfast. The wife of the Head Coastguard had identified them. A remarkable achievement in that this operation was carried out without any casualties on either side. By July 1st 1921 he would have been a seasoned veteran of guerrilla warfare. On page six of his pension application dated 8th of April 1935 under the heading:

(7). Continuous Active Service during period 1st April, 1921, to 11th July, 1921

(f) Particulars of any military operations or engagements or services rendered during the period (he writes the following in his own hand) Culleens attack on RIC, capture of arms & killing of some of the RIC in the battle.

The Republican memory - 14 years 7 months later

Q. Ambush of RIC patrol and capture of same at Culleens. Were you on this yourself ?

A. I was on all these myself……….

Thomas Loftus [14] appeared before the Advisory Committee on the 5th of February 1936 and submitted his sworn statement in support of the application form he had completed on the 7th of May the previous year. An active Volunteer in the North Mayo Brigade, he had also participated in the successful capture and destruction of the Enniscrone Coastguard Station in August 1920.[15] As previously mentioned by Matt Kilcawley, Thomas Loftus was one of the men who had carried out the initial robbery on the pub and shop at Culleens on the morning of the ambush. What I found striking about his application in comparison to others, would be the lack of detailed questioning from the Advisory Committee regarding particular actions that the applicant had included in his written submission. On page six, in one line he lists the Culleens ambush, in the following line he adds “shooting of Sgt Foody[16] RIC at Bonniconlon.” He was not questioned about Sgt Foody or his role in the shooting. Another point of interest would be the fact that it is the only action I can find in the North Mayo Brigade Activity Report which does not list the men involved.

The Republican Memory-14years 7months later

Q. What exactly happened – were you close up ?

A. Yes I was.

Q. How close ?

A. Within 40 yards. What happened was we raided a house in the morning, took all the money in the shop, I was one of the two people who went in to take it, and the son went in to notify the robbery and while they were away we handed it back to the sister.

In contrast to the applications completed by some of the other men involved in the Culleens ambush Jack Brennan[17] doesn’t have enough space on his form to include all that he was involved in from joining the Volunteers in April 1918. In his sworn statement given before the Advisory Board on the 9th of December 1936, he explains how he had heard that members of the North Mayo Brigade were camping in the mountains a distance of about 15 miles from his home. He visited the camp and offered to take part with two of his comrades from Sligo Brigade, his offer was accepted. His statement is invaluable in that he admits to being one of men who carried out the robbery. He describes the arrival of the RIC patrol at the scene, the fact that he was armed with a rifle (which he fired) but critically he mentions his actual position in the ambush and that he was placed near to where the patrol would have to turn into the pub and shop.

The Republican memory - 15 years 7 months later

“They pursued us into the heart of the Ox mountains, it was a running fight that lasted from 12 o’clock until nightfall”.

Dr. Martin Brennan[18] in a sworn statement submitted to the Military Service Pensions Board on the 1st of February 1937 was questioned about his involvement in the Culleens ambush. He explained that the day before the ambush along with Seamus Kilcullen he had raided the mail at Dromore West and commandeered food in the hope of getting the RIC out of the barracks to investigate so that they could launch an attack on them. The patrol did not materialise on this occasion. He went on to describe the robbery at Culleens the following morning and that he thought there were eight to ten in the patrol which arrived at the scene but that only five came within the firing line. He further stated that two RIC men were killed and one wounded, he had been armed with a rifle on this occasion. He also gives a good sense of what must have been a frantic running gun battle which lasted until dusk. Martin Brennan also confirms that he was a participant in the Chaffpool ambush on the 30th of September the previous year which resulted in the death of 21 year old RIC District Inspector Brady (who was the son of the Assistant Harbour Master of Dublin and nephew of Mr. P. J. Brady ex-MP for Stephen’s Green)[19] and the wounding of Head Constable O’Hara, he further states “I fired about four (rounds) I think one of them got the Head Constable in the leg because they put out reports that we had dum dum bullets and we thought it was the bullet from that thing that got him, he had to get his leg amputated”. Martin Brennan fought on the Republican side during the Civil War, amongst the many actions he participated in was the Rockwood ambush of the 13th July 1922 in which four Free State soldiers were killed and the armoured car Ballinalee captured. In April 1923 he was arrested under arms with two of his comrades by Free State forces while visiting the mother of a local Volunteer who had died in an accident in Kildare. A neighbour reported his presence to the Free State forces. With the house surrounded, and the mother and sisters of the deceased in the house, the men surrendered. While being held in Claremorris Workhouse Martin Brennan was sentenced to death, this sentenced was reprieved following the intervention of Patrick Morrisroe, Bishop of Achonry. Following a forty two day hunger strike he was released in July 1924.[20]

Reports of an ambush - 3 days later

In the days following the ambush there were various newspaper reports of the events at Culleens. The Anglo Celt,[21] The Irish Independent[22] and The Donegal News[23] all included one paragraph on the ambush. The Western People[24] published a more extensive piece eight days later, but the most detailed account of the events leading up to and the subsequent gun battle on the bog following the killings of John King and Thomas Higgins were covered in The Irish Times[25] published on the 4th of July 1921. Under the headline “Numerous ambushes, Seven policemen dead, Shocking crime in Co. Sligo, A kidnapped Constable’s fate” The newspaper quoted an official report issued from Dublin on the day following the ambush. It described how the RIC patrol of seven had been ambushed by two different groups separated by several hundred yards. It named Constable Carley as one of the injured RIC men and how he had been wounded in both arms. The comprehensive report also mentioned that on the arrival of British Military reinforcements from Sligo and Ballina, that a running fight across the bog then took place for a number of hours. It also mentions in this report the presence of a large number of civilians engaged in cutting turf during the exchanges of fire between the Volunteers and British Military and that a number of horses and cattle were killed by gunfire. “The Crown Forces eventually abandoned the fight when they considered that further pursuit was useless”.

I could not find any report on the funerals of John King or Thomas Higgins.

The official memory - 2 days later

“The matter is reported to the Military and Police in Sligo and a party of Police and of “C” Company are rushed to the scene and join in the pursuit until the rebels are lost in the bog and the search is abandoned.”[26]

The British Army war diary for 1st Battalion Bedfordshire & Hertfordshire Regiment notes the robbery carried out at a public house in Culleens and that the raiders take £271 in notes and silver. It describes how the robbery was reported to the RIC barracks in Dromore West and that a patrol of seven was sent to investigate. It also tells us that during the ambush one of the RIC boarded a passing car and had the driver take him to Easkey barracks for assistance. Ten men from Easkey barracks arrived at the scene of the ambush at 1.30pm and immediately began to search for the ambush party. Within a short time they could see the group of Volunteers and came under fire from them. Fire was returned and the pursuit continued. At 3.30pm the two captured men who are in front of the main group of Volunteers are seen to fall. When the patrol from Easkey reach the spot, one constable is dead and the other is close to death. They have both received gunshot wounds to the back. Their arms and ammunition have been taken by their captors.

The Official Memory-one day later

Courts of Inquiry in lieu of Inquests

“I produce the bullet which I found in the clothing of Constable John King when I was undressing the body”[27]

I discovered this file in the British National Archives early in 2020, I found it to be a powerful document of the events of that day. The Court of Inquiry was held on the day following the ambush, and the venue was the Barracks that the patrol had left from. The enquiry had been ordered by Lt. Colonel Thorpe of Boyle who was in command of the

The first witness was Sgt Michael Healy 57323 he was the Sgt in charge of Dromore West RIC Barracks. He began his evidence by stating that Thomas Higgins was from Caltra, Ballinasloe, Co. Galway and that John King was from Fairgreen, Roundstone, Co. Galway. Sgt Healy went on to detail the report given by Thomas Tuffy at 10.30am the previous morning, that two armed men had entered his father’s shop at 8.30am that morning and had stolen the cashbox which contained £261. Immediately on receiving this report Sgt Healy ordered a patrol of five constables and another Sgt to join him. They set out towards Culleens with Thomas Higgins and John King at the front of the patrol. As they neared the scene of the robbery, they were ambushed. Remarkably, he states that “myself and the others in the patrol with the exception of the two deceased got clear of the ambush I did not see the two deceased again until their bodies were brought into the Barracks last evening. I identify the two bodies which the court have just viewed as being the bodies of Thomas Higgins and John King. Both Constables were single men.”

The second witness was District Inspector W. E. White[28] RIC Ballina. In his evidence he described receiving a wire from Easky RIC Barracks at around 1pm alerting him to an ambush in progress at Culleens. He gathered a patrol of around twenty men and when they arrived on the scene they had to proceed for a further couple of miles before they could see, in the distance a group of 20 men with two men at the front, District Inspector White believed that the two men at the front were the RIC men. “While I was watching them and before we opened fire, these two men appeared to fall, and one of my men shouted to me that he had heard firing.” At this point he describes how they opened fire on the group of men and gave chase. He also noted that some of his group remained behind with the bodies. He completed his evidence by stating that he continued the pursuit for another four or five miles, but never came any closer than eight hundred yards from the group of “Rebels.”

Sgt George B Anderson 60840 from Easkey RIC Barracks was the third witness. In his evidence he describes how he was part of a section under the command of District Inspector White who were in pursuit of those who had ambushed the patrol at Culleens “About three and a half miles from where the ambush occurred, I came across the body of Constable Thomas Higgins who was dead, and also that of Constable John King who was dying. They were lying two or three yards apart. Both had bullet wounds in the right breast. Constable John King died about two hours after this. I was with him at the time”. Before he died, Constable John King told Sgt Anderson that the patrol had been ambushed by upwards of thirty men, and that he had been shot in the back while the group were being pursued across the bog.

The fourth witness was Dr Henry Mark Scott Medical Officer of Easky No. 2 Dispensary District. He described how he had received a message at 5.30pm the previous day to say that he was required at Culleens. On arrival he saw a lorry containing two bodies. He followed the lorry to Dromore West RIC Barracks and identified the bodies of John King and Thomas Higgins. He first examined the body of John King and found four bullet wounds in the back and one at the front, he managed to extract a bullet from the body of John King which he produced at the inquiry. He then examined the body of Thomas Higgins and found two bullet wounds in the back and one at the front. He further stated that in both cases the wounds inflicted in the back were entrance wounds and those at the front were exit. He completed his evidence with the following “In my opinion the cause of death in both cases was due to shock and haemorrhage caused by the wounds I mentioned above”.

The final witness was Constable James Hoy 72424. In a brief statement, he describes how at 8.30pm the previous evening he had discovered a bullet in the clothing of Constable John King while undressing his body. He believed, that from the condition of the bullet, it had passed through John Kings body.

Finding:

The court having carefully considered the evidence brought before it having examined the two bullets produced before the court (which were those of a 450 revolver) are of opinion that Constable Thomas Higgins and Constable John King both of the RIC stationed at Dromore West Co. Sligo

1. Died from shock and haemorrhage caused by gunshot wounds on July 1st 1921.

2. That they were murdered by some persons unknown.

President

Lt Colonel WRH Dann DSO

Members

Lt D. Rhys Thomas MC

1st Battalion Bedfordshire & Hertfordshire Regiment.

Lt J.C.M. Taylor

1st Battalion Bedfordshire & Hertfordshire Regiment.

Aftermath

Ten days later, at precisely the time that the firing had started at Culleens, the firing ceased in the Irish War of Independence, as the Truce came into effect at 12 midday on the 11th of July 1921. The implications of the Truce for those who had participated in the Culleens ambush were unprecedented, as it provided them with immunity from arrest and prosecution. But that is not to say that there were no arrests in connection with the events of that day, one man was arrested on the day of the ambush and was to spend over five months in prison until his release on the 9th of December 1921. Thomas Tuffy, who had reported the initial robbery to Sgt Michael Healy at Dromore West RIC Barracks (and was completely innocent of any involvement in the ambush) was arrested as a suspected accomplice and held in Sligo Gaol before being transferred to Ballykinlar Internment Camp.

Jack Brennan went on to play senior football for Co. Sligo and was chairman of the Sligo County Board from 1947 to 1950 and vice-chairman of the Central Council of the GAA. He was an umpire at the famous 1947 All-Ireland final held in New York between Cavan and Kerry. A founder member of Co. Sligo Races Ltd. and the Tubbercurry Industrial Association. He was the father of one son and four daughters. He died on the 21st of March 1974, fifty two years and eight months after the ambush.

Thomas Loftus emigrated to America in 1925 and returned to Ireland in 1932. On his return he joined the Garda and quickly gained promotion to Detective Branch in Dublin Castle. In April 1938 he accompanied de Valera to London for talks with the British Government as part of his protection unit. He was appointed Captain of the Guard in Leinster House in 1947 and Superintendent in 1960. He was the father of six children, three of whom entered religious orders. He died on the 9th of January 1967, forty five years and six months after the ambush.

Edward Gildea took the Republican side during the Civil War, he took part in the Republican capture of Ballina on the 12th of September 1922. After the detonation of a landmine at the Post Office which had been commandeered by Free State forces (as it had an uninterrupted view of the main thoroughfare) he entered and removed a machinegun and thirteen pans of ammunition for use by the Republican forces. The following month his Civil War would be over. He was travelling as a passenger in a truck when they were surprised by a party of Free State soldiers, not having an opportunity to fight his way out, he was captured close to the RIC barracks in Dromore West from where the RIC patrol had left the year before. He was held in Athlone Military barracks for six months and was then transferred to Mountjoy Gaol where he remained until his release at Christmas 1923. Edward Gildea worked as a stonemason, he never married. He died in April 1961, thirty nine years and ten months after the ambush.

Tommy Tuffy returned to work after his release from Gaol and built a thriving business at the site of the original robbery and ambush. He was a much loved and respected member of the community from which he came from, proof of this can be seen in the full page of coverage given to his death in the Sligo Champion of the 9th of May 1959. Tommy Tuffy was the Father of five sons and two daughters. He died on the 2nd of April 1959, thirty seven years and eight months after the ambush.

Sgt Michael Healy who received the initial report of the robbery at Culleens on the morning of July 1st 1921 retired from the RIC on its disbandment. He was the father of one son and two daughters. He died on the 29th of October 1957, thirty six years and three months after the ambush.

Dr. Martin Brennan went on to become a Fianna Fail TD for Sligo/Leitrim from 1933 to 1948 and was appointed Film Censor in 1954. He was the father of two sons and a daughter, he died on the 21st of June 1956, thirty four years and eleven months after the ambush.

Matt Kilcawley went on to become a successful businessman and managing director of Messrs. Kilcawley & Co. building contractors. He was the father of five sons and one daughter. He died on the 10th September 1955, thirty four years and two months after the ambush.

The RIC Memory[29]

"On 1st July 1921 a police cycle patrol was ambushed and fired at near Culleens Co Sligo. Constable Carley was wounded by bullets in both arms. The wound in the right arm was a bad one and he has been non-effective from the effects of it ever since."

In the new state which emerged after the War of Independence, Republicans who had participated in armed actions against the Crown Forces were given an opportunity to detail in official archives the part they had played. The pension applications are also an archive of social history in that they give us a window into the lives of those in the decades following the conflict and tell a story of economic hardship and struggle for some. They also tell us when the applicants died.

For those Irishmen who had served in the RIC, there appears not to have been the same urgency or opportunity to record and detail their experiences of the conflict. Above all else, it appears that anonymity was what they wanted. But one individual felt strongly enough in 1956 to submit an account from a different perspective of an ambush which had taken place in a neighbouring county two months before Cullens on the 3rd of May 1921. Mr. JRW Goulden[30] had been born in the RIC Barracks in Tourmakeady in 1907, and was the son of an RIC Sgt. stationed there. The ambush[31] resulted in the deaths of four RIC men and one member of the IRA, (Mr. Goulden’s father survived the ambush) in his account of the Tourmakeady ambush gleaned from conversations with the survivors, he describes the following “Oakes was killed at once, but Sergeant Regan and Flynn were wounded. Flynn told me that he was lying near the gate and could see under the car. The attackers then came running and began to disarm Regan and Oakes. He heard someone say: “you summoned me for a light once Regan” and then he shot him. I did not hear this from Flynn until some time afterwards, but my father told me that there was a gaping hole in Regan’s stomach from which rags of his clothing, which were shot into the wound, protruded.” The bodies of the four RIC dead, Constable’s Power, O’Regan, Oakes and Sgt. Regan were taken to Ballinrobe RIC Barracks, where the then thirteen year old JRW Goulden viewed them with his mother. On the evening of the ambush, as was customary, two businesses in Tourmakeady and a number of vacant houses near the site of the ambush were destroyed in reprisal. In the final paragraph of his submission Mr. Goulden states that a number of days later his father was ordered to burn the house belonging to the mother of a dead IRA member[32] in Cross. He refused to carry out this order and resigned.

As a result of the anonymous lives lived after the conflict, the records which do exist give us the details and background prior to and during service with the RIC but come to an end with disbandment. One can only then imagine what the years following were like for the men who had served with the RIC.

Sgt. Michael Healy 57323 was born on the 26th of June 1874 in Cornelock, Killala, Co. Mayo, he was the son of Bryan Healy, a farmer and Ellen Brown. He was a Catholic and had enslisted on the 22nd of November 1895. He was recommended by District Inspector Kieser, on enlistment he was 21 years and 4 months. He was 5ft 10ins and his occupation was given as farmer. His first assignment was to Cork West Riding on the 29th of May 1896, and then Sligo 15th May 1903. He was promoted to Sergeant on the 1st of October 1920 and disbanded on the 6th of April 1922 in Sligo aged 47 with 27 years service. He had an annual pension of £195. Michael Healy had served in Strandhill 1910-11, Tubbercurry 1916-19, Sligo 1920 and Dromore West 1921.

District Inspector William Eugene White was born 13th August 1893 in Strokestown Co Roscommon, he was the son of Michael White, shop keeper, and Bridget Geraghty he was a Catholic and enlisted in the RIC in 1920; assigned to Ballina Co Mayo on 17th August 1920; appointed Cadet 15th June 1920; District Inspector 3rd 7th Aug 1920; District Inspector 2nd 7th May 1921; he had served as Lieutenant in the R.F.A. Favourable record for gallant conduct at Bonniconlon 3rd April 1921;[33] paid up to and for 6th April 1922; discharged on pension on disbandment of RIC; awarded annual compensation allowance of £129-12-7 from 7th April 1922. He had connections in Roscommon, Kings County and Dublin; he married Belinda Mary Angela Ryan on 13th August 1920 in St Joseph's Catholic Church, Terenure; he was of full age, bachelor, commissioned RIC officer, based in RIC Depot, Phoenix Park, son of Michael J. White, gentleman farmer; Belinda was of full age spinster, from 32 Rathgar Avenue, Dublin, daughter of Michael Ryan agent Army Service; Service No 101637; Enlisted in Royal Field Artillery on 1s Jan 1916 from Athlone giving his grandmother, Mrs Margaret White, 5 Temple Road, Dublin as his next of kin; he served in Athlone, Woolwich & Dublin, Alexandria and Mesopotamia. He was absent from the Guard room while on Railway Bridge guard in Athlone on 27th March 1916 and absent from parade in Woolwich on 18th June 1916; he was in India 7th July 1916; Mesopotamia 1st August 1916 to 20 May 1918; Egypt 8 Jun 1918-23 Jun 1919; He received the British War Medal & British Victory Medal on 16th November 1920 [he signed a receipt with the address Palace St, Dublin]; he was demobbed on 29th September 1919 from Woolwich, aged 26, with tinnitus and a disability to his right index finger, rated 5% disabled, and awarded 5/6 weekly pension. He wrote to the regiment on 12th Nov 1919, seeking a reference for a temporary job in the Dublin Post Office;"

George Benjamin Anderson 60840, was born in Naas Co Kildare on 20th Nov 1883, he was the son of James Anderson, RIC constable and Eliza Weir. He enlisted from Cork East Riding on 1st July 1902, recommended by District Inspector Moriarty; on enlistment aged 18 years, 7 months, he was a Protestant; assigned Waterford 15th Jan 1903; Cork East Riding 1st Nov 1903; Co Kerry 21st Sep 1905; Reserve 1st Nov 1906; Co Clare 31st August 1907; Co Sligo 1st October 1915; promoted to Sergeant 1st Feb 1921; disbanded 6th April 1922; allowance £195. He married Mary Dundon in SS Peter & Paul RC Church, Kildysart, Co Clare on 28th July 1915. The marriage certificate states that he was an RIC constable, stationed in Cappaskilla, Fountains, Ennis, son of James Anderson, RIC constable. Mary was from Kildysart, daughter of Thomas Dundon, shopkeeper.

James Hoy 72424 was born 24th Feb 1899 in Largalinney, Churchill District, Co Fermanagh, he was the son of John Hoy, care taker, and Bridget Duffy he enlisted in the RIC on 11th August 1920, recommended by District Inspector Carroll; on enlistment he was 5ft 8.25ins, he was a Catholic, occupation ex army officer. He was assigned to Sligo on 29th October 1920. He was disbanded on 4th April 1922, and received an allowance of £50-14-0.

Eugene Carley 67100 born 17th July 1891 in Kinnegad Barracks, Co Westmeath, he was the son of Owen Carley, RIC Sergeant and Anne Hughes. He enlisted 17th February 1913, recommended by District Inspector Foy. On enlistment, he was 5ft 8.1ins, no occupation was given. He was discharged as unfit on 19th Feb 1913, and was reappointed on 4th August 1914, and assigned to Sligo on 25th Feb 1915. He was fined 10/- on 5th Feb 1920. he was pensioned on 25th Jan 1922 on the ground of being unfit for service as he had suffered a bullet wound in the "right upper arm with nerve involvement producing weakness & limitation of movement of the right arm and a near useless right hand received on duty" His annual pay at the time was £218-8-0 and he was given a pension of £42-12-9. The pension document also records "On 1st July 1921 a police cycle patrol was ambushed and fired at near Culleens Co Sligo. Constable Carley was wounded by bullets in both arms. The wound in the right arm was a bad one and he has been non-effective from the effects of it ever since"... additional note "At Sligo Quarter Sessions on 27 September last the constable was awarded £2000 compensation under the Criminal Injuries (Ireland) Act.

John King 63068 born 7th May 1885 in Errisbeg, Roundstone, Co Galway, he was the son of Patrick King, deceased farmer, and Bridget Toole. He enlisted from West Riding, he was a Catholic. Enlisted 26th Sep 1907, recommended by District Inspector Irwin. He was 6ft 2.5ins, occupation farmer. He was assigned to Co Mayo on 15th Feb 1908, Belfast on 11th Aug 1912, Sligo 1st Dec 1915. He died on 1st July 1921 "murdered by rebels". He served in Kelworth 1910; Ballincurrig 1911-1915; Ballymoghenry 1916-1917 & 1919; Cliffony 1918; Chapelfield 1920; Dromore West 1921. According to his death certificate, he was aged 36, bachelor, RIC constable, died 1st July 1921 at Culleens, from shock and haemorrhage caused by gunshot wounds.

Thomas Higgins 67230 born 10th Dec 1883 in Graigue, Mountbellew, Co Galway, he was the son of Thomas Higgins, farmer and Maria Duffy. He enlisted from Galway East Riding on 1st July 1907, recommended by District Inspector Richmond. On enlistment he was 5ft 9ins, he was a Catholic, occupation farmer. He was assigned to Co Sligo on 5th Dec 1907; he served in Riverstown 1911; Keash 1911-1918; Dromore West 1919-1921; he died on 1st July 1921 - murdered by rebels. His death cert states he was aged 37, single, occupation RIC Constable, died 1st July 1921 in Culleens, Co Sligo, cause of death, shock and haemorrhage caused by gunshot wounds.

Conclusion

Reflecting on the experience of standing in a remote spot high up on a bog in west Sligo with Martin John Dolphin and listening to what he had been told about the events which took place there a century ago, confirm for me the importance of oral history and memory. This perspective can be another lens with which to view the events as they unfolded and used in conjunction with all the other archive and published material to give in some instances, insights only available to those who were present on the day. Rebecca Graff-McRae[34] while addressing the subject of truth and memory, quotes Lewis Namier: “One would expect people to remember the past and imagine the future. But in fact, when discoursing or writing about history, they imagine it in terms of their own experience, and when trying to engage the future they cite supposed analogies from the past; till, by a double process of repetition, they imagine the past and remember the future.”

In an attempt to examine and explore the events which took place, I have consulted the available archive material held within the Irish and British collections. Of note within the Irish Military Service Pension Collection, there are currently twenty-nine applications which reference the ambush. The Brigade Activity Report[35] for the North Mayo Brigade includes details of the ambush. It names twenty-nine men as being involved in the initial ambush, and another forty-one on outpost duty.

From the various accounts recorded, it appears that the first shots were fired at 12 noon. Within half an hour Constable’s Higgins and King were captured and disarmed. From the British Court of Inquiry File, we can see from District Inspector White’s evidence that he received information at 1pm in Ballina that an ambush was in progress at Culleens. We don’t have the precise time that he arrived on the scene with twenty reinforcements, but shortly after his arrival and sighting of the group with the two Constables in front, both men were seen to fall.

Given the passage of time, and a better understanding of the impact events such as the Culleens ambush can have on those who witnessed, those who participated and those who suffered. It is important to be sensitive to the different memories and truths that are held.

It is difficult to imagine a more powerful symbol of memory, than this six-foot square of uncut turf in a remote bog in west Sligo.

A goal for me while researching this ambush was to also make contact with the family of at least one of the RIC members who survived the ambush. I am grateful to the family of Sgt Michael Healy for contacting me, I hope that they now have a fuller picture of events as they unfolded on the 1st of July 1921, and a better understanding of why Michael Healy could never speak about it afterwards.

In an essay which accompanies the introduction to the publication of war photographer Don McCullin’s retrospective collection of some of the most powerful and moving photographs of conflict and human suffering from the 20th century, the distinguished novelist, essayist and author Susan Sontag states the following:

“I would suggest that it is a good in itself to acknowledge, to have enlarged, one’s sense of how much suffering there is in the world we share with others. I would insist that anyone who is perennially surprised that depravity exists, who continues to experience disillusionment (even incredulity) when confronted with evidence of what humans are capable of inflicting in the way of gruesome, hands-on cruelties upon other humans, has not reached moral or psychological adulthood.

No one of a certain age has the right to this kind of innocence, of superficiality, to this degree of ignorance, of amnesia.

We now have a vast repository of images that make it harder to preserve such moral defectiveness. Let the atrocious images haunt us. Even if they are only tokens and cannot possibly encompass the reality of a people’s agony, they still perform an immensely positive function. The image says: keep these events in your memory.”[36]

Dedicated to the memory of Martin John Dolphin, and all who witnessed and lived with the legacy of events at Culleens on Friday the 1st of July 1921.

© Frank Fagan University College Cork MA Local History 2021.

[1] Interview conducted by author with Pat Ruane 11th March 2018

[2] Jackie Clarke Collection, a private collection of over 100,000 items of Irish historical interest gifted to the people of Ballina by local businessman and Republican Jackie Clarke 1927-2000.

[3] Interview conducted with Pat Ruane for the Mayo News in 2016 published 9th June 2020 “There’s a big question mark over that. My aunt said she heard a commotion outside. Politics was very hot at the time, meetings were being broken up. The official line was that something electrical was left on. I have my doubts.”

[4] Michael Farry The Aftermath of Revolution Sligo 1921-23 University College Dublin Press 2000

Michael Farry Atlas of the Irish Revolution Cork University Press 2017

[5] Ernie O’Malley The Men Will Talk to Me Mayo Interviews Mercier Press 2014

[6] Richard Abbott Police Casualties in Ireland 1919-1922 Mercier Press 2000

[7] Jim Herlihy The Royal Irish Constabulary A short history and genealogical guide with a select list of medal awards and casualties Four Courts Press 2016

[8] Anne Dolan Death in the Archives: Witnessing War in Ireland, 1919-1921 The Past and Present Society, Oxford, 2021.

[9] Interview conducted by author with Martin John Dolphin 17th May 2018

[10] Ernie O’Malley The Men Will Talk to Me Mayo Interviews Mercier Press 2014 Interview with Matt Kilcawley page 239 “We did not cut the wires or anything either to excite or alert the RIC”.

[11] Ernie O’Malley The Men Will Talk to Me Mayo Interviews Mercier Press 2014 page 241

[12] Ibid page 239

[13] Military Service Pension 34REF12006

[14] MSP34REF9456

[15] Bureau of Military History Witness Statement 1683 Patrick Coleman page 10

[16] Ex RIC Sgt Foody was abducted in Bonniconlon and shot dead on the 6th of July 1921.

[17] MSP34REF33559

[18] MSP34REF38562

[19] Donegal News 9 October 1920

[20] Pauric J. Dempsey Dictionary of Irish Biography Brennan Martin

[21] Anglo Celt, 9 July 1921.

[22] Irish Independent, 6 July 1921.

[23] Donegal News, 9 July 1921.

[24] Western People, 6 July 1921.

[25] Irish Times, 4 July 1921.

[26] Bedfordshire and Luton Archives and Records Service, Bedford. Capt. A.L. Dunnill A Summary of Events during the period in which the 1st Battalion Bedfordshire & Hertfordshire Regt. was stationed in Ireland 1920 1921 1922

[27] Courts of Inquiry in Lieu of Inquests WO35/151A/72 British National Archives Constable Thomas Higgins & John King RIC Culleens Co. Sligo.

[28]Five week earlier, on the 25th of May 1921 North Mayo Brigade IRA had attempted to kill District Inspector White as he was driving with his wife in Ballina. The ambush failed, and in a search operation the following morning an eighteen year old Volunteer from Enniscrone Thomas Howley was fatally shot by a member of the RIC.

[29]Information kindly received from Kay MacKeogh Academic/ Researcher/Genealogist /Royal Irish Constabulary 1816-1922 A Forgotten Police Force.

[30] Bureau of Military History Witness Statement 1340

[31] The Irish Times 6th May 1921

[32] The Irish Times 9th May 1921 South Mayo Ambush, second body identified.

[33] Irish Independent 5th April 1921. Refers to a late night ambush on an RIC patrol in which Constable Hawkins was seriously wounded. Thomas Loftus confirms that he was a participant in this ambush.

[34] Rebecca Graff-McRae Remembering and Forgetting 1916 Commemoration and Conflict in Post-Peace Process Ireland Irish Academic Press 2010

[35] A35 2 North Mayo Brigade, 4 Western Division.

[36] Susan Sontag “Witnessing” Don McCullin Jonathon Cape Random House London 2003 page 17.

April 14th, 2021 marks the centenary of one of the most significant and tragic events of the War of Independence in Ballina.

On this day one hundred years ago, 26-year-old Ballina native Michael Tolan was arrested and subsequently endured a most brutal and gruesome death at the hands of British Crown Forces.

The shocking tale of the arrest, disappearance, and tragic discovery of the mutilated body of Michael Tolan remains one of the darkest chapters in our town’s recent history.

A tailor by trade, Tolan was born with ‘reel feet’-a deformity which caused his feet to turn in and affected his walk.[1]. At the time of his murder, he was a Non-Commissioned Officer for the North Mayo Brigade IRA, an intelligence officer, recruiter and a ‘summons server’ for the local arbitration courts (known as the ‘Sinn Féin Courts’). He was a bachelor and lived on Shamble Street.

Tolan had been involved with nationalist activities in Ballina from early 1917, when a branch of the Irish Volunteers and a Sinn Féin Club were established in the town. In his Witness Statement to the Bureau of Military History, Stephen Donnelly recalled days of his youth in the Ballina unit of Fianna Eireann: “Tolan...took complete charge of us. He has us affiliated with Fianna Eireann in Dublin & took all the necessary instructions from there”. [2]

Ballina of one hundred years ago was a town firmly in the grip of the ongoing ‘Troubles’. The notorious ‘Black and Tans’, sent as reinforcements to the local RIC, had become a feature of everyday life in Ballina and patrolled the streets regularly and with great zeal. They were joined in January 1921 by the Auxiliary Division RIC (‘The Auxies’); easily identified by their distinctive uniforms and ‘Tam-O-Shanter’ beret-style caps. Crown Forces established their HQ at the Imperial Hotel on lower Knox Street. A strictly enforced curfew between the hours of 8pm and 4am was set. The Union Jack flew high atop ‘The Imperial’ as local merchants, publicans and residents endeavoured to carry on with their lives in the streets below.

In July 1920, just eight months before the arrest of Tolan, local members of the North Mayo Brigade carried out a daring ambush on the nightly RIC patrol at Moy Lane, just one hundred yards from the barracks on Charles Street. The skirmish resulted in the fatal shooting of RIC Sergeant Thomas Robert Armstrong. A fifty-six-year-old Cavan native and father of eleven children, Armstrong had served in the town for twenty years and was held in high regard by the townspeople. Reporting on the incident, ‘The Ballina Herald’ noted the tragedy of the fact that Armstrong, “who was always looked upon as most inoffensive officer” was due to begin his retirement in matter of weeks.[3] The killing of Armstrong was a turning point in the town and signalled a drift towards violence on both sides of the conflict.

In the weeks and months leading up the arrest of Tolan, ‘tit-for-tat’ actions and counteractions by the IRA and Crown Forces characterised life in Ballina and its hinterland. Raids on homes and businesses, intimidation, armed patrols, and regular weapons searches (even outside Mass) were the order of the day.

In January 1921, during an arms raid on Becketts Mills, prominent Brigade member Pappy Coleman was captured and severely beaten at the Charles Street Barracks.[4] Less than three weeks later, Brigade officer, solicitor and Chairman of the Ballina Urban District Council PJ Ruttledge (who went of the serve as a Fianna Fáil TD for thirty-one years and three-time cabinet minister) was arrested, court-martialled and sentenced to six months in Galway Jail.[5] Such was the “bad handling” he received that he was left deaf in one ear for some time afterwards.[6]

Owing to the ongoing hostilities, Tolan, like so many of his comrades, was ‘on the run’ at time he was ‘picked up’ and was in the habit of staying in various homes to avoid capture. On the night of 14h April 1921, he was at the home of Mr. and Mrs. Forbes of Shamble Street- a house in which he had sought refuge many a time before. When the Crown Forces arrived at the back door, Tolan -in his bare feet- made for the front door but was captured a few yards from the house. He was brought to the RIC Barracks, until an order for his interment could be procured.

Local Cumann na mBan members, Ida O’ Hora and Margaret Sweeney, were among the first to visit Tolan at the Barracks. There they found him lying in a cold, dark cell, still in his bare feet and moaning in pain. Miss Sweeney later said he was unable to eat the food brought to him, such was his condition. Tolan told her that his jailors had nearly killed him. Supplies of food, warm woollen socks, boots and an overcoat were quickly sourced and brought to the Barracks. A heavy overcoat-dark green in colour-supplied by Ida O’ Hora was later to become a key piece of evidence at the inquest into Tolan’s death.[7]

On her first visit to see her son (“my boy”, as she called him), Tolan’s widowed mother Mrs. Ann Quigley could scarcely make out the face of her curly-haired son in the darkened prison cell. On the second occasion, Michael was permitted to approach the door of the cell, allowing his mother a better, and as it transpired, final look upon her son before his disappearance. [8]

As Tolan languished in his cell, his comrades in the North Mayo Brigade continued in their struggle against his captors. On the night of 15th April, Bridge Street was the scene of a planned ambush of the RIC patrol by a small band of local men. When the patrol was ordered to halt, an exchange of gunfire ensued. Two Constables- Walter Davis and Harold Moore were severely injured. The patrol was forced to retreat to the nearby barracks for safety.[9]

In an act of retaliation, the Crown Forces embarked on a frenzied rampage through the town centre. Shop front windows, places of businesses and homes were smashed. Weapons were fired indiscriminately, leaving the commercial centre of the town in a sea of broken glass and bullet casings. We can but image the treatment of prisoner Tolan in the aftermath of the ambush and it seems likely that he too bore the brunt of the rage administered that night.